Introduction

Consensus is a key component to providing fault-tolerant services such as synchronously replicated data stores, non-blocking atomic commitment and Paxos and Raft are among the most popular consensus algorithms. Paxos has been widely studied by researchers while Raft has become very popular among engineers.

The Raft’s popularity comes from the fact that despite all the interest around Paxos among researchers, engineers still have to read several papers to be able to understand and create a solution that solves a practical problem and provides good performance in terms of communication steps, number of messages and resource utilization. Besides, they still have to fill in some gaps with home-made implementations that sometimes turn out to be really fragile.

In order to overcome this hurdle, Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout created a new consensus algorithm called Raft which was designed to be more understandable and provide a better foundation for building practical systems than Paxos [2]. Although Raft brings some novelty to the complex world of Distributed Systems, it still shares a lot of things in common with Paxos. For example, both elect a single leader which is responsible for deciding whether the participants in the consensus have reached an agreement or not.

In this blog post, we will briefly show the similarities and differences between Paxos and Raft. Firstly, we will describe what a consensus algorithm is. Secondly, we will describe how to build a replication solution using instances of a consensus algorithm. Then we will describe how leaders are elected in both algorithms and some safety and liveness properties.

Note that this blog is not a deep dive into Paxos nor Raft but an overview on both algorithms. Users willing to understand their subtle details should read the following papers: [1, 2, 3, 4].

Consensus

Distributed systems can be characterized by a set of safety and liveness properties or the mix of the two. Informally, safety is a property that stipulates that nothing bad happens during execution of a program. On the other hand, liveness stipulates that something good eventually happens.

In consensus, whose goal is to make a set of servers agree on a value, the liveness is characterized by the fact that eventually every server should decide on a value. Safety states that no two servers decide differently.

Unfortunately, a server may take longer to execute an algorithm step than others and may crash and stop processing the consensus algorithm. Messages might get delayed, delivered out of order or dropped. These aspects make the implementation of a consensus algorithm really hard and oblige them to be indulgent and preserve safety during ‘instability’ periods [5]. Exactly when the system will become ‘stable’ though is unknown but eventually it will remain ‘stable’ long enough so that the consensus algorithm can achieve a decision.

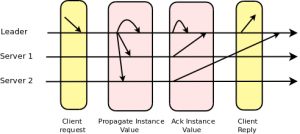

In a stable run, the system requires two communication steps: leader –(1)–> servers –(2)–> leader:

The leader sends the value it wants to achieve an agreement on to all servers and each server replies back to the leader notifying that it has accepted the request. So when the leader gets accept messages from a quorum of servers, agreement is reached.

Note that we have omitted two messages from this analysis: the message that forwards a value which a server wants to reach an agreement on to the leader and the message that informs servers that an agreement on the value was reached. The latter message may not be necessary if servers send the accept message to all servers or the information is piggybacked in the next message the leader sends to the servers.

Replication

In order to implement replication, several instances of a consensus algorithm are run and each instance is bounded to a slot entry in the replicated log which might be persisted on disk or not [6]. The leader may run several instances in parallel to fill in different slots and thus increase performance. However, the degree of parallelism is highly dependent on the hardware, network in use and the application [7].

Each leader is uniquely responsible for a round or term which is monotonically increased when a new leader is elected:

Leader Election

Both Paxos and Raft assume that eventually there will be a leader that all stable servers trust and a single leader is responsible for a term. A new leader will propose a new term, which must be greater than the previous one, if the current leader is suspected to have failed.

In Raft, a server sends a “leader request” to other servers and expects a reply from a majority of them before considering itself a leader. If it does not get a reply from a majority of servers or a message saying that another server has become the leader, it will timeout and start over a new election process. Servers can only vote for one leader request per term.

Paxos, though, does not really define how a server becomes a leader. For simplicity, researchers exploit the a-priori rank among processes such as the server’s id (e.g. an integer). So the server with the highest or the lowest rank that has not been suspected becomes the new leader [8]. Although, this is a simple and intuitive solution, it requires to divide the terms’ space among servers: new term = old term + N, where N is the maximum number of servers.

Raft imposes a restriction to the leader election process: only the most up-to-date server can become a leader. Basically, it guarantees that a leader has all committed entries from previous terms and does not need to learn about old entries in the replicated log that it is not aware of. So after becoming a leader, a server can simply start “imposing” its “wishes” on other servers.

Paxos, however, allows any server to become a leader. So a server has to learn about the past before starting “imposing” its “wishes” on other servers and as usual, flexibility comes along with additional complexity.

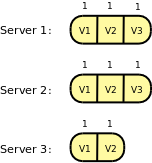

In Raft, either Server 1 or 2 could become a leader. In Paxos, any of them.

Safety

Due to the asynchronous nature of the system, servers may perceive failures and elections at different times. This means that servers may temporarily operate in different terms but eventually all servers will converge to a single term.

In any case, if a server gets a message from a term older than its current one, this means that the sender either was the leader or is trying to become one for an old term and the receiver must reject the message and inform the sender.

If a server gets a message from a term greater than its current one, this means that there is a new term and a new leader and the receiver must start accepting the leader’s “wishes”.

However, both algorithms must carefully avoid overwriting a decision made by an old leader and thus violating safety. This is where Raft and Paxos diverge and where we can see the simple and elegant approach used by Raft.

Raft imposes restrictions on the leader election algorithm as aforementioned and only the most up-to-date server can become a leader:

Raft determines which of two logs is more up-to-date by comparing the index and term of the last entries in the logs. If the logs have last entries with different terms, then the log with the later term is more up-to-date. If the logs end with the same term, then whichever log is longer is more up-to-date.

Then the leader only needs to ensure that the replicated log in the servers eventually converge, which is done by imposing the following restriction: A server cannot accept a value for slot "n" if it has not previously accepted a value for slot "n - 1". The leader includes the term of the previous log entry in the current request and the server only accepts the request if the term of its previous request matches the one sent by the leader. Otherwise, it asks the leader to send the previous missing request first, and so forth for "n - 2" and "n - 3", etc.

In Paxos, any server can become a leader so that the task of avoiding that a decision is not overwritten becomes a little bit more complex as the new leader leader has to find out what other servers have processed so far before starting “imposing” its “wishes” on others. This is the prepare phase in the Paxos algorithm and has to be run once after the new leader is elected. The prepare message contains the new term and the slot number "n" through which agreement has been reached for all previous entries. Servers reply with information on slots greater than "n" and this information is used to restrict the values that the new leader will propose for these slots.

Liveness

Progress is guaranteed as long as the majority of servers are alive [9].

Conclusions

We have shown the similarities between Raft and Paxos and that the key difference relies on how a leader is elected and preserves safety. In Raft, only the most up-to-date server can become a leader while Paxos allows any server to become a leader. This flexibility, however, comes along with additional complexity.

Note that the leader in both Raft and Paxos might become a bottleneck as all the traffic goes through it. The leader handles O(N) message while a non-leader handles O(1).

There are other Paxos-based protocols that support multiple leaders such as Mencius [10] or order non-conflicting requests in parallel such as Egalitarian Paxos or Generalized Paxos [11, 12]. It would be great to see Raft-based protocols with similar optimizations.

References

1 – Paxos made simple

2 – In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm

3 – Desconstructing Paxos

4 – Yet Another Visit to Paxos

5 – Consensus in the presence of partial synchrony

6 – Failure Detection and Consensus in the Crash-Recovery Model

7 – Tuning paxos for high-throughput with batching and pipelining

8 – Introduction to Reliable and Secure Distributed Programming

9 – Lower Bounds for Asynchronous Consensus

10 – Mencius: Building Efficient Replicated State Machines for WANs

11 – There Is More Consensus in Egalitarian Parliaments

12 – Generalized Consensus and Paxos